The Story of Mary Dean’s School – established 1722

This is an update from a booklet by by P.S. Bebbington

Who was Mary Dean and what kind of person was she? We only know part of the answer to these questions. No portrait of her is thought to exist and the outline sketch below is taken from a coat-button (see below) of the clothing worn by the pupils of the school she founded.

She was the eldest of three daughters of Sir James and Lady Elizabeth Modyford, and had one elder brother who died young. Much of her life was spent at Maristow near Tamerton Foliot. Her father lived abroad a great deal, becoming Deputy Governor of Jamaica, where he died and was buried in 1673. Mary can have seen very little of him for she spent most of her life close to her mother. There is no evidence that either of them ever went out to Jamaica. All trace has been lost of Mary’s sister Elizabeth, but her youngest sister Grace married and brought up a family in the West Indies.

Mary married John Dean(E) about 1683, and they had a daughter Elizabeth who in turn married and had a son. Mary became a widow in 1702 and within a few years she also lost her daughter, son-in-law and her grandson. Mary lived to the age of 74 years, her nearest relatives then being nephews and nieces.

Mary had helped her mother to found schools at Buckland Monachorum (1702) and Walkhampton (1719). It is not surprising then to find Mary herself interested in doing the same. In 1720 she bought a house in Tamerton Foliot for this purpose, and her mother’s Will says that a school had been started there within two years.

Mary’s grandfather, Sir Nicholas Slanning, owned large estates at Bickleigh, Buckland, Maristow and Walkhampton. Mary helped her mother with the management of these estates which later passed to her sister Grace. Long after Grace’s death, the family sold the estates in 1798 to Lord Roborough’s family. Lady Elizabeth, Mary Dean and John Dean(e) are all buried at Bickleigh Church, near Plymouth.

Mary Dean’s School was established in 1722. Today, about 330 children go into Mary Dean’s school every day. The School has its own website https://www.marydeansprimaryschool.co.uk/

When the school was started, only twenty boys were allowed in, which Mary Dean felt was as many as the money she provided would support.

This was almost certainly Tamerton Foliot’s first school. The richer families were able to employ a tutor for their children, or pay to send their sons away to be educated, but very little had been done for other children. Most of the children in the parish never had the chance to be educated at all. They spent their whole lives unable to read or even sign their name, except by putting a cross.

About the year 1700, people began to think that children should be taught to read and write, and to read their Bible. If they could do so it was thought they would grow up into better citizens, be more contented, and less likely to poach or steal, or spend their time begging.

Setting up a Charity School, with funds provided by benefactors with money to spare was considered the best way to help. A number of such schools were opened in Devon including those founded by Mary Dean’s mother with help from Mary herself, at Buckland Monachorum and at Walkhampton. Both ladies were widows, and lived together at Maristow for many years. In 1720 Mary Dean bought a house in Tamerton Foliot, in which she started the school that bears her name, though it was not endowed until her death in October 1734.

THE OLD SCHOOL

This school was in the house that is now called “Hillside”, on Whitsoncross Lane. At that time it was known as the School House, and was on School Hill. Mary Dean set up the school “for a period of two thousand years”, so she clearly intended that it should last long enough to do its job properly! To support it she left the sum of £480, as well as the rent of a farm in Tavistock. This covered the schoolmaster’s salary, buying fuel for the schoolroom fire, and also the purchase of books and materials for the pupils, as well as their clothing.

The school remained in this house for 140 years, until 1877. This is a picture of what it probably looked like.

Every year, each of the twenty boys was given what was probably the best outfit of clothes he would ever have. It included a coat of green cloth, a waistcoat, a pair of breeches (knee-length trousers), two shirts, two pairs of shoes, two pairs of stockings, a cap, a pair of woollen gloves, and two neckbands with white tabs at the front (like those still worn by some clergymen).

This was similar to the clothing given to pupils in other Charity Schools, and we know from pictures of the time, (about 1750), that the boys must have looked rather like this in their school clothes.

The school was controlled by two people called trustees. It was their responsibility to appoint the schoolmaster, and select the pupils. Mary Dean had said these were to be “Twenty poor boys from the parish, and no more”, and they were to be taught to read and write, to learn arithmetic, and to be instructed in their principles of the Christian religion. They were known as “The boys on the Foundation”. They started at age seven, leaving after three or four years at most, when they went straight out to work, usually on the land.

The boys might come from anywhere in the parish, those from Blaxton or Broadley had to walk several miles over rough tracks, often deep in mud. Sometimes in winter the weather was so bad they stayed away. In December in 1879 the teacher wrote, “Children coming in very cold, had to warm them….. Washed several children who came dirty, and then they hardly knew themselves.”!

Cleanliness seems to have been a recurring issue. A later entry reads, “Sent Sam Woodley outside to wash, and threatened to scrub him before the girls if he comes dirty again.”

THE SCHOOL DAY began at seven in the morning in summer, and lasted for eight hours; in the winter it began an hour later and finished an hour earlier. Children from a distance would bring something to eat at midday, often a potato which they would put in the ashes of the school fire to bake. There was schooling six days in each week, with a few days holiday at Christmas, Easter and Whitsuntide, and usually four weeks in the summer.

The schoolmaster also had to take the boys to church every Sunday and every Holy Day. His salary was £20 a year, and included the use of the school house, and the produce of its garden. Some masters earned a little extra for training the church choir, or writing letters for people in the village. This was poor pay even for those days, but because there were not many such posts available, the masters tended to remain at the school for many years. The second one to be appointed, Richard Hutton, stayed for over 30 years. He was then given the sack because the trustees thought him too old and infirm to carry on.

Mary Dean left very clear instructions as to what should be taught, and how the children were to be divided into four groups. All the work was done in the one classroom. a long narrow room with a fire at one end near where the master sat. The scholars sat on forms. facing the master, and for many years all their writing was done on slates. On the walls were large cards on which were printed letters of the alphabet, used for teaching the beginners. Much of the work was learning by heart, through repeating aloud after the teacher. As all were together in the same room, it must often have been very noisy, with the beginners chanting, some of the others perhaps reciting tables, and the master himself questioning the older pupils.

If proof is needed that the first school was in the house called “Hillside”, the name of William Smith, (who was master from 18171847) is scratched on the inside of a window, where it can still be seen. This was presumably done by his daughter Mary, aged 12, in April 1826. Further evidence is the entry in the 1840 Tithe Map showing the school building.

Mary Dean made provision only for boys, which is strange because some Charity Schools already admitted girls. But it was not until 1798, nearly seventy years later. that the first girls came to Mary Dean’s school. and then ten were admitted. This increased the number of pupils to thirty. and the schoolmaster’s salary was also increased to £30 a year. which perhaps is why no money could be found by the Charity to provide any special school clothing for the girls.

This is a copy of the only list to have survived of the boys and girls then in the school, showing the different dates at which each started:

Soon after 1800 the number of girls went up to 15 and the master’s salary was raised to £35 a year. He was allowed to take a few private pupils which added to his salary but the number of children was seldom more than 40. A woman teacher was employed to help out. In the churchyard there can be seen a memorial stone to Mrs. Ann Moon.

Other schools were opened in Tamerton at this time, which is not surprising as there were certainly many more children in the parish. There was a girl’s “Subscription School” in 1821, also a boarding school for boys. This was called, “Mr. Howard’s Classical School... and survived about 20 years. There was a “Parochial School” for boys and girls from about 1839, which gave full-time education and was held in the old Warleigh Room beside the church. The Parochial School was closed in 1877, and combined with Mary Dean’s school pupils in a new building at Rock Hill. The Warleigh room was pulled down in 1971 to make way for the new Church Hall.

The girls seem to have preferred the Parochial School — perhaps they liked the two women teachers better than Thomas Brewer, who was the master at Mary Dean’s. At all events, he was left with only four or five girls although there were plenty of boys; in fact, in 1865, his classroom was widened to accommodate more pupils.

At this time there were also dame schools, where generally the teaching was of a much lower standard. There were probably two in Tamerton, and they were popular because of their low price of a halfpenny or a penny a week. They were usually held in the front room, or even the kitchen, of a cottage. Sometimes those in charge could hardly read or write themselves, and so did little more than mind the children and keep them occupied. Two private schools in the village were closed in 1889; these were probably Dame Schools.

Sunday schools thrived too in Tamerton. They were provided at Mary Dean’s and the Parochial school, as well as separately by the Wesleyan Methodists.

ROCK HILL SCHOOL

Then something happened which changed the picture completely. In 1870 Parliament passed the Education Act. and Elementary schooling became compulsory for all children. This meant that many more school places would be required. The Government provided some money for this, but most had to be paid by the local people out of rates or taxes.

The parishioners in Tamerton decided on a bold move. They asked permission to combine Mary Dean’s with the Parochial school, closing down the old buildings and replacing them with a larger one at the top of Rock Hill. The new school was planned to hold 140 children, in two classrooms, with a house for the headmaster. Much of the money for this came from Mary Dean’s Charity.

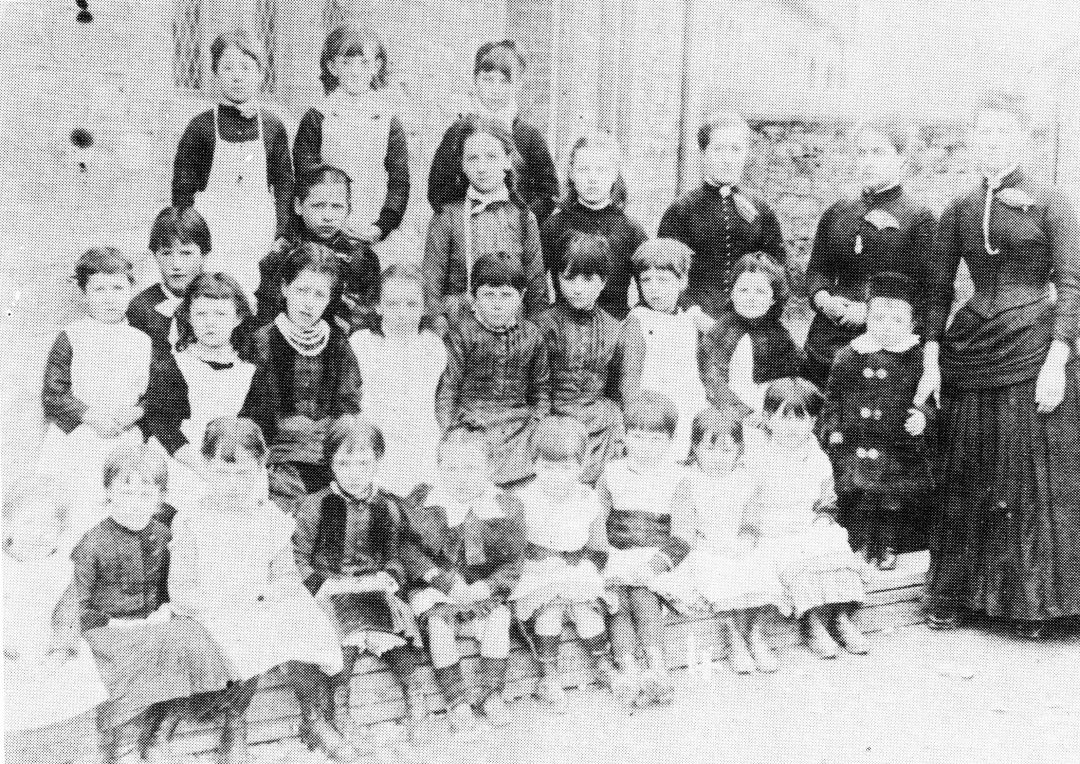

The school was opened in April 1877, with a new master and mistress called John and Emily Walters. Thomas Brewer had retired, after 30 years in the post. There was a new Governing body, and a lot more children. The 70 older children were in the larger classroom, the boys at one end and the girls at the other. They were taught by the master with a Pupil Teacher (learning the job), and a monitor (one of the older pupils who might one day become a Pupil Teacher).

The Inspector’s report on that first year said, “The promising beginning in discipline and attainments has been well carried out. The tone of instruction seems to be zealous and industrious. The importance of neatness and cleanliness should be constantly impressed on the children. More room is needed in the gallery, and desks and some permanent and efficient addition to the staff of teachers should be obtained as soon as possible”.

“The gallery” was a raised platform in the second room, which in all had to accommodate about 60 infants. The infants were allowed to start school when they were three or four years old. Sometimes a mother would try to slip one in who was even younger, if perhaps she was hard-pressed with a large family. One entry in the headmasters log-book reads, “Sent Ellen Pedrick home as she is not yet three. Have discovered her mother entered the wrong age, so as to get rid of the child.”!

For a long time there was a shortage of desks. and many children must have sat on the floor. Gradually desks with fixed tops seating six were brought in, and remained in use until the 1920’s. Inspections were held twice a year. In April a clergyman came to test the children’s religious knowledge. The October examination was an even more important occasion, when a government inspector came to the school. If his report was good, the master’s pay might be increased, otherwise it could be reduced. No doubt this caused a lot of tension, and some of the children would be so nervous that they would stay away for the day. This did not help matters. because the inspector’s report was based on good attendance as well as good examination results. The examination was in dictation, composition, reading and arithmetic; the girls were also tested in sewing and needlework.

The infants log books between 1777 and 1900 often refer to sewing and needlework, which was regularly inspected by the Vicar’s wife. Sewing included “Making shirts for the older boys”,. also “fraizing”, which meant pulling out the threads from old material, and using it as a stuffing for pillows.

Singing was mentioned too, and we have the titles of some of the songs. “Raindrops” seems to have been a favourite and had a part for solo voice and chorus. Other titles given are more unusual. There was “The disobedient chicken”; “The boy who told a lie”; an action song called “Exercise bone and muscle”; and one called “Hurrah, Hurrah for England”.

An important part of school learning was “The Object Lesson”. This meant a number of set topics were studied over a period, with a test at the end. To us, the selection of subjects may seem rather strange. One list reads: “Fishes; Hooks and Eyes; Chalk; Birds; Flies; Beaks of Birds; Storm at Sea”. Another list adds, “Have had to alter some lessons, thus Zebra and Gum-Tree, not having any text books for same”. Some of the Object Lessons were of a more practical kind. We find included, “Preparations necessary for a garden for vegetables”, “House cleaning”; “How to dress a doll”; and “A Visit to the seaside”. Other activities mentioned in the log books under “Varied Occupations” are: “Colouring; Stick Laying; Paper Folding, Darning;. Basket Making; Bead Threading and Fraizing.” School life could not have been too humdrum!

The records sometimes give us glimpses of day to day life in the school, brief though they are. The children were not so overawed by discipline as we might think. We read of apple cores being thrown across the classroom. and children sent home for “disgusting behaviour”, — though we’re not told what that was! Once a headmaster thrashed two boys for fighting, and the next day the mother of the one boy marched into the classroom. and in front of the headmaster and class, boxed the ears of the other boy for getting her son into trouble. Another incident happened when the infants were going home. A cow, perhaps frightened by older boys, ran down Rock Hill, and seriously injured three children as well as a little girl from the Dame School. Twice, the school bell, which was fixed on the roof, fell out of its mounting, and crashed on to the school yard. Fortunately no-one was hurt. The bell now hangs in a safer place, in the entrance hall at Jessop’s Park.

SICKNESS too, such as measles, scarlet fever, bronchitis, croup and whooping cough caused many children to miss schooling. There is one touching entry in the school records as late as September 1916 which reads, “Shall we ever be free from diptheria, there is very little interval between the cases”. Disease spread quickly in the village, partly as a result of its poor water supply, and its bad drains. Chiefly perhaps, it was due to the overcrowding in the cottages, where as many as six or eight could be sleeping in one room.

Occasionally the headmaster gave the children an extra holiday. One regular entry in the log-book is, “Closed the school this afternoon for the Tamerton Regatta”. This annual water carnival was held on the Creek, and was very popular. Other regular events were the Sunday School teas, and the Band of Hope tea. More unusual is the entry, “So few children attended school today, due to a fashionable wedding, that I decided to close”. Perhaps his wife and the other lady teacher wanted to go along and see the pretty dresses!

In 1933 the school was closed early on the occasion of a village Fruit Banquet, which may have been the beginning of the annual Strawberry Feast, still held in the village.

Occasionally ten or eleven year-olds were admitted who had never been to school before, and entries like “June 1st, 1894 Admitted Audrey Hicks — a girl nearly eight years of age, not knowing the alphabet”, are quite common. Life must often have been difficult for teachers having to cope with children whose parents, in some cases, could neither read nor write. For the benefit of such people, there used to be, in the 1890’s, readings in the schoolroom on Wednesday evenings. These were organised by the Vicar, and were often crowded out. They were known as Penny Readings, because one penny was charged for admission.

In winter the classrooms were often very cold. There was only one stove in each room, and it didn’t always burn properly. In summer it could be too hot, and on one occasion boards were removed from the ceiling to improve the ventilation !

In 1891, an extra classroom was built for the senior boys, which was paid for out of Mary Dean’s Charity. This meant the school could now take more than 200 pupils. Unfortunately it came too late, because numbers began to fall through families leaving the village for work elsewhere, so that for a number of years the school was little over half full.

In 1902 there was another big change. The new Devon Education Committee took charge of the school, and appointed its own managers. Mary Dean’s Charity endowment and its Governors became quite separate, concerned in future only with giving financial aid where needed, but still owning the building in which the school was run.

From the time of Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee in 1887, events in the world outside were reflected in the school log books. The school was closed to celebrate the Relief of Mafeking in 1899, and Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee. On the coronations of Edward VII and George V, the children were given a tea-party with sports and a bonfire.

May 24th was Empire Day, and in 1909, a flag-staff was put in the school yard, so that the children could mark the occasion by saluting the Union Jack and singing patriotic songs. Since 1890 the children had been taught military drill as a form of physical recreation, though it ceased for a time during the Boer War (1902) when no drill sergeant was available. During the First World War, the school raised money to help the Sick and Wounded Horses, and collected for the Russian Red Cross.

At the George V Silver Jubilee, and at the Coronation of George VI, they received commemorative mugs and medals.

Just before the outbreak of the 1939 — 45 war, the seniors were transferred to other schools. Mary Dean’s was then solely an Infant and Junior school. Arrangements were made to bring in other children from outside the village. Some came from Whitleigh. others from Glenholt, and in September 1939 these were joined by children evacuated from London.

In April 1941, the rear part of the school was taken over by the police to give shelter to the homeless from Plymouth and Devonport, as a result of the air-raids on the city. Although the school escaped any serious damage, the log books report that, “Constant interruptions from air-raids are seriously affecting school work.” In that same month, thirty-two bombs exploded within a few hundred yards, but the school suffered only shattered windows, although part of the ceiling in the schoolmaster’s house was brought down. The school again made its contribution to the war effort. Boxes of eggs were sent to the hospitals, and money was raised for Servicemen’s Charities; thus, in May 1944, £243 was collected for “Salute the Soldier” week.

It was difficult to get caretakers during the war, and the Headteacher and his wife spent part of their summer holiday in 1943 scrubbing out the classrooms. To celebrate victory in 1945, the children were given commemorative mugs and entertained to tea and sports with fireworks in the evening.

After the war, there were about one hundred children attending the school. They were in three classes, and taught by the Head-teacher and two women assistants. A report by an inspector reads, “The behaviour of the children in this school is easy, friendly and courteous. For this, and for the simple delight which they appear to take in their work, great credit is due to the Headmaster.” (Mr. Hooper)

Between 1953 and 1966 school numbers declined still further, but then began a steady upward trend, rising to three hundred by 1975. This naturally created problems in the now out-dated and over-crowed school building in Rock Hill.

THE SCHOOL AT JESSOP’S PARK

Fortunately, by this time, the site for a new school had been bought in fields at the top of the village, now known as Jessop’s Park. After a number of frustrations and delays, the school moved there in October 1975. It was opened officially by Lord Roborough in May of the following year, and was dedicated by the Bishop of Plymouth, thus reaffirming the school’s religious foundation.

Opening Ceremony of the New Mary Dean’s School on 27th May, 1976

It was officially opened by Lord Roborough and he can be seen at its entrance with the headmaster, Mr. Ellis and Vicar of Tamerton Foliot Reverend Christopher Goodwin. Many village children are watching the service of dedication led by the Bishop of Plymouth. Mr. S. Luke

In other ways, though, how different from its beginnings! Space, light, colour, warmth in winter, playgrounds, sports-fields, a kitchen to provide hot meals, and all kinds of equipment — that is the background for the children at the school today.

A parent-teacher association was formed in 1967, which continues to give the school much appreciated support.

Mary Dean’s School Foundation is an active Registered Charity. https://register-of-charities.charitycommission.gov.uk/charity-search/-/charity-details/306781 The charity provides funding to Mary Dean’s school to a budget set each year by the Trustees. Grants to former pupils of the school who are undertaking further/higher education or need sponsorship for a recognised activity to an amount set by the Trustees.

Children are now admitted at five, and stay until the September after their eleventh birthday, when they transfer to secondary school.

“Where once they learned with tears now they learn with pleasure.” (C. Milne —`The Path through the trees.” p.189).

Let us hope that something valuable from their formative years spent in this school, will remain with them for the rest of their lives.

Headmasters (Headteachers)

These six were Masters in the first school building

| Richard Martyn | October 1734 | June 1750 |

| Richard Hutton | June 1750 | June 1784 |

| John Light | June 1784 | December 1798 |

| Thomas Smith | January 1799 | March 1817 |

| William Smith | April 1817 | September 1847 |

| Thomas Brewer | October 1847 | March 1877 |

The new school opened at Rock Hill on 9th April 1877

| John Walters | April 1877 | July 1.879 |

| Thomas W. Jones | September 1879 | April 1880 |

| G. R. Stanlake | May 1880 | May 1882 |

| W. H. Mitchell | May 1882 | July 1884 |

| Thomas J. Bennetto | August 1884 | October 1893 |

| Walter H. Brown | October 1893 | April 1902 |

| Evan W. Lukis | May 1902 | October 1925 |

| Henry G. Symons | April 1926 | June 1931 |

| Vernon C. Hooper | June 1931 | December 1952 |

| Miss M. Nicholson | April 1953 | December 1965 |

| Ray L. Ellis | January 1966 | ? |

The new school opened at Jessops Park in October 1975

| Nigel Sparrow | ? | 2013 |

| Tracey Jones | 2013 | 2022 |